A Case of Anchoring Bias

If you’ve been following the blog so far, you know that clinical decision making is a complex process prone to many errors, including cognitive biases (ways our thinking can systematically lead to errors). We all have inherent cognitive biases – that’s part of being human. We are more prone to cognitive bias when we are using our intuitive thinking to reach conclusions about patient information (i.e. system 1 thinking) instead of our analytic thinking (i.e. system 2 thinking) (1). If you haven’t already done so, read our first blog post on diagnostic reasoning which introduces the important concept of dual process theory – i.e. system 1 and system 2 thinking when making clinical decisions.

What are cognitive biases? “Systematic errors in thinking due to human processing limitations or inappropriate mental models” (1). In other words, our brains process information inaccurately at times, more often than we would care to admit. Logically this makes sense - we aren’t perfect at processing information.

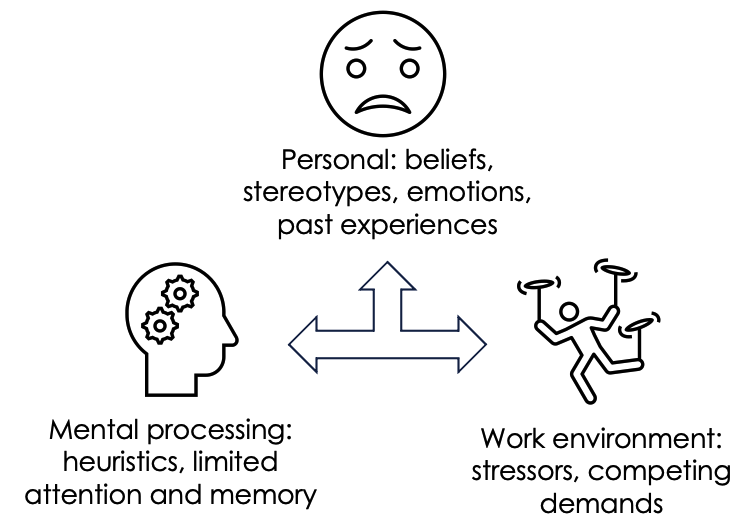

Why do cognitive biases occur? Our brains receive overwhelming amounts of information on a daily basis. To cope with this, our brains like to simplify this information. System 1 thinking is an easier thinking pathway as it takes less mental effort. It has been proposed that cognitive biases are more likely to occur when using system 1 thinking, or when system 1 thinking overtakes system 2 thinking (1, 3). Many factors play into cognitive bias - personal beliefs, stereotyping, emotions, past experiences, heuristics (taking mental short cuts to make decisions quickly), limits to the mind’s attention and memory, and work environment - to name a few.

How do cognitive biases affect patient care? Not surprisingly, they are implicated in making diagnostic errors and can lead to subsequent patient harm (2). There is a long list of cognitive biases, and several can occur at once, some we are more prone to, and others less so. Common biases include anchoring, premature closure, confirmation bias (3), affect heuristic, outcomes bias, overconfidence, and availability bias (4).

We will introduce the concept of cognitive biases with a case study, starting with the anchoring bias.

Case: A patient reports bright red blood when wiping after bowel movements. On assessment an external hemorrhoid is found. The clinician diagnoses an external hemorrhoid and prescribes treatment. During a follow up visit a month later, the patient continues to report bright red blood per rectum, and it seems to be getting worse. They have been using treatment as prescribed. The clinician reassures them that hemorrhoids can take time to heal.

Can you pick up on the cognitive bias happening with this clinical encounter? It is easy to anchor onto the first diagnosis we make – but if a patient is not responding to treatment as one would expect, we should think twice about the initial diagnosis.

Definition of anchoring bias: clinicians prioritize information that supports their initial impressions, even when first impressions may be wrong. The clinician relies on the first piece of evidence too heavily and fails to seek additional data that may refute their first impression, even when more information becomes available (2).

Back to the case: The same patient returns a month later, still reporting bright red blood when wiping after having a bowel movement daily. This time, a different clinician is assessing them. The clinic day has been extremely busy. The clinician sees from the chart that external hemorrhoids were previously diagnosed, and prescribes them a different medication in the hopes it will clear the hemorrhoids.

Anchoring bias can be passed not only from appointment to appointment, but from one clinician’s assessment to another. It is very common to anchor onto someone else’s diagnosis, if previously made. This can be because we can be inherently trusting in our colleagues’ assessments. This commonly happens in clinical practice.

How to we manage cognitive biases? Some authors have referred to a process called “cognitive de-biasing” (5,6). Simply put, it is being able to catch and correct our mental biases. We are faced with many high-risk situations in clinical practice that subject us to cognitive biases. How do we fix this? First, we need to identify cognitive biases as they occur in real time (or reflect on cases after the fact). Second, we can learn from our mistakes (no one is perfect!) and employ strategies to mitigate these biases. The easiest way to do this – ask yourself questions.

Asking a few key questions can quickly challenge the anchoring bias in this case scenario: Are we sure about the initial diagnosis? What is the worst thing it could be and have we ruled it out (e.g. cancer)? Could it be something else – e.g. inflammatory bowel disease, infection? Asking these questions can a) challenge our cognitive biases, and b) help us come to the right diagnosis.

Some other questions we can ask, depending on the clinical situation: Was the diagnosis suggested to me by another clinician? Did I accept the first diagnosis that came to mind? Do I have bias towards this patient? Am I stereotyping the patient? Have I been interrupted or distracted while evaluating this patient? Am I feeling fatigued, emotionally exhausted, or did I sleep poorly last night? Am I experiencing cognitive overload right now? Am I ordering something just to appease the patient? Have I ruled out the must-not-miss diagnoses? Am I jumping to conclusions?

Key Take Home Points:

Biases are inherent and unavoidable. The good news? We can challenge and try to limit these biases during patient encounters.

Anchoring bias is common in clinical practice – if a patient is coming back with symptoms that are not improving (or getting worse) – ask yourself, what else could it be, and have I ruled out the worst-case scenario?

References/Readings

Hammond MEH, Stehlik J, Drakos SG, Kfoury AG. Bias in Medicine: Lessons Learned and Mitigation Strategies. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2021 Jan 25;6(1):78-85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.07.012. PMID: 33532668; PMCID: PMC7838049.

Dargahi H, Monajemi A, Soltani A, Hossein Nejad Nedaie H, Labaf A. Anchoring Errors in Emergency Medicine Residents and Faculties. Medical journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2022;36:124-.

Saposnik, G., Redelmeier, D., Ruff, C.C. et al. Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 16, 138 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1 (VIEW HERE)

Kunitomo K, Harada T, Watari T. Cognitive biases encountered by physicians in the emergency room. BMC emergency medicine. 2022;22(1):1-148.

Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 1: origins of bias and theory of debiasing. BMJ quality & safety. 2013;22(Suppl 2):ii58-64.

Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 2: impediments to and strategies for change: Diagnostic Error in Medicine. BMJ quality & safety. 2013;22.