Elevated ALT: Causes and Evaluation

Lab Test Interpretation Pearls for the Nurse Practitioner

Case: you open your inbox and review a mild ALT elevation of 60, for a 50-year-old male patient. What do you do with this result?

What is ALT?

Alanine aminotransferase is an enzyme found mainly in the liver (but also found in tissues such as the heart, muscle, and kidneys) (1). Elevated ALT serum levels may signify hepatocellular injury, as damaged hepatocytes release ALT into the bloodstream (1, 2). Elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) serum levels can also indicate hepatocellular damage, but can also be caused by thyroid disorders, hemolysis, celiac disease, muscle disorders (amongst other diseases) (2).

ALT Reference Ranges

Reference ranges differ due to variability in lab reporting, and the definition of "normal ALT" is inconsistent across the literature. This is why understanding lab reference ranges is crucial, so we can use our clinical judgement to interpret results. When interpreting ALT, here are a few tips to keep in mind:

ALT levels are higher in males than females (3)

ALT levels vary depending on BMI and serum lipid levels (3)

ALT levels fluctuate during the menstrual cycle (3)

In the absence of risk factors for liver disease, normal serum ALT ranges from 29-33 IU/L (males) and 19-25 IU/L (females) (3)

There is no fixed cut-off for “normal” ALT and each lab reports different ranges

The first thing to ask yourself is why ALT was ordered in the first place.

ALT is ordered for a multitude of reasons - for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Sometimes we didn’t originally order the ALT, and we are following up for another provider.

When is ALT ordered in asymptomatic patients? The most common reason in primary care is to monitor patients for drug-induced liver injury (e.g. with medications such as HIV antivirals, antifungal drugs, methotrexate, etc.). Historically, baseline ALT levels were checked before initiating statin therapy. Recent guidelines suggest against checking baseline ALT prior to statin initiation in healthy, asymptomatic patients without other risk factors (e.g. known hepatic disease, taking other medications that inhibit CYP450) (4). Other considerations may include patients who have alcohol use concerns, to screen for alcohol-related liver disease (3).

In reality, ALT may have been ordered by another provider for unknown reasons - but you might be the one needing to follow up on the abnormal result. Or sometimes ALT is re-ordered based on a previously elevated ALT and is simply being trended over time.

When is ALT ordered in symptomatic patients? There is a long list of potential reasons - and it all depends on the patient’s presentation and your pre-test probability for various conditions! We will focus on mild, asymptomatic ALT elevations, as this is a common conundrum in primary care.

Back to the case: why was ALT ordered? You are following up on this abnormal result - however you were not the provider who originally ordered it. You do some detective work in the patient’s chart. You scroll back to the patient’s last encounter and read a previous provider’s documentation note: “ALT previously noted as elevated, will re-order to re-assess and trend.” There are no notes to indicate that the patient is symptomatic.

Differential Diagnosis for Mildly Elevated ALT in Asymptomatic Adults

It can be helpful to think about your differential using three categories: common causes, uncommon causes, and rare causes of mild ALT elevation.

MAFLD

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is the most common cause of asymptomatic ALT elevation (3). MAFLD can be divided into two sub-types:

Non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis without inflammation: is defined as intrahepatic TAG (fat/lipids) of at least 5% of liver weight or 5% of hepatocytes containing lipid vacuoles in the absence of a secondary contributing factor (e.g. excess alcohol intake, viral hepatitis) (5). Liver steatosis is graded based on the percentage of fat within the hepatocytes: grade 0 (healthy, <5%), grade 1 (mild, 5%-33%), grade 2 (moderate, 34%-66%), and grade 3 (severe, >66%) (5).

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: this is characterized by hepatocyte injury with ballooning, inflammation, and in severe causes can lead to fibrosis and cirrhosis (3).

BOTTOM LINE: Differential diagnoses to consider for asymptomatic mild ALT elevation include MAFLD, alcohol use, medication-induced, viral hepatitis, hemochromatosis, and other rare causes (Wilson’s disease, autoimmune hepatitis, AAT deficiency).

Clinical Assessment Pearls

When you see the mildly elevated ALT, work through your differential diagnoses. If ALT is more than 2x the upper limit of normal, it is even more imperative to rule out other causes of liver disease.

MAFLD: look for clues of metabolic syndrome - does the patient have insulin resistance, pre-diabetes or diabetes? Do they have dyslipidemia or hypertension? What is their BMI and waist circumference?

Alcohol-related liver disease: review previous and current alcohol use using standard drink measurements.

Medication-induced: review their medication list to look for possible culprits.

Viral Hepatitis: do they have any risk factors for hepatitis B or C? Review country of origin (endemic regions for hepatitis), concurrent HIV infection, history or current injection drug use, household contacts or sexual partners with known hepatitis (3).

Hereditary hemochromatosis: is there a family history of this disease? Do they have any clinical manifestations? (e.g. excessive fatigue, joint pain, erectile dysfunction, bronze skin, abdominal pain) (3).

Alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency: do they have early-onset emphysema, or a family history?

Autoimmune hepatitis: do they have concurrent autoimmune disorders? (3)

Wilson disease: typically young persons with neuropsychiatric symptoms, Kayser-Fleishcer rings (3).

Assess for stigmata of liver disease, including: spider angiomas, jaundice, palmar erythema, gynecomastia, ascites, encephalopathy, and asterixis.

Back to the case: your patient has risk factors for MAFLD including a BMI of 35, pre-diabetes, and dyslipidemia. Otherwise there are no known risk factors for other liver disease. He denies alcohol use. You suspect MAFLD.

Should I Order Further Lab Testing?

Once you’ve worked through your differential diagnoses, you can tailor further diagnostic testing.

Here are some general tips for your initial work-up:

Since MAFLD is the most common cause of mildly elevated asymptomatic ALT, order an up to date lipid profile and hemoglobin A1C if not on file. If results are elevated, this can help tailor treatment to target metabolic risk factors.

Hepatitis B surface antigen and Hepatitis C virus antibody testing is pertinent to rule out viral hepatitis (patients can be asymptomatic).

Ferritin can be ordered to rule out hereditary hemochromatosis.

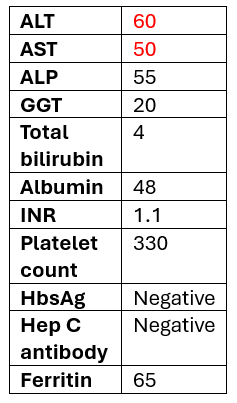

It is also reasonable to order other liver enzymes and liver synthetic tests to identify any common co-existing liver disease, and to detect potential complications of suspected MAFLD (tests may include: AST, +/- ALP, GGT, Albumin, total bilirubin, INR, CBC with platelets).

It is helpful to have an AST to determine the AST:ALT ratio. If the AST:ALT is >2, alcohol-related liver disease is suspected, with a positive likelihood ratio of 17 (3).

THE BOTTOM LINE: MAFLD is the most common cause of mildly elevated ALT in asymptomatic adults. Assess for metabolic risk factors, including A1C and lipid profile. You can start with ruling out other causes of elevated ALT with the following labs: AST, GGT, ALP, total bilirubin, albumin, INR, platelet count, HbsAg, Hep C antibody, ferritin.

What is the Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) Index?

The FIB-4 score is a validated index used to risk stratify patients with MAFLD into high, intermediate, and low risk of developing cirrhosis over the next 10 years (6). It can also be used to assess the risk of liver fibrosis in patients with any known risk factors for liver disease such as alcohol-related liver disease (6). Given the variable progression of MAFLD, it is important to assess those at risk of more advanced disease because it can affect how often you monitor these patients, and may alter treatment (3).

Why use FIB-4? While liver biopsy is the gold standard to diagnosis liver fibrosis, it is invasive and has risks. The FIB-4 index is a superior non-invasive marker of fibrosis in patients with MAFLD and can be used to trend risk over time (6).

How do I calculate FIB-4? You need the patient’s age (use with caution in patients <35 years old or >65 years old), ALT, AST, and platelet count. (MD CALC FIB-4)

What do the FIB-4 scores mean? If the FIB-4 is low risk (advanced fibrosis excluded), it can be recalculated every 2-3 years. If intermediate or high risk (advanced fibrosis cannot be excluded), refer to a specialist (7).

THE BOTTOM LINE: Use the patient’s age, ALT, AST, and platelet count to calculate a FIB-4 score which assesses risk of liver fibrosis. If low risk, re-measure every 2-3 years. If intermediate-high risk, consider hepatology referral.

Back to the case: You order the following tests and review results.

Numbers in red are abnormal (elvevated)

Next, you calculate the FIB-4 index to estimate risk of liver fibrosis, result: 0.98 points (advanced fibrosis excluded). You are assured that advanced fibrosis is excluded, and ask whether diagnostic imaging is indicated.

Should I Order Diagnostic Imaging? Liver Ultrasonography vs. Elastography (FibroScan)

Liver ultrasonography: In order to diagnose MAFLD, there needs to be one metabolic risk factor identified (e.g. elevated hemoglobin A1C, dyslipidemia, BMI >25, high blood pressure) (8). Second, a right upper quadrant ultrasound can be arranged to diagnose steatosis (8). If steatosis is identified - there is your diagnosis of MAFLD. Note that ultrasound lacks sufficient sensitivity for lesser degrees of steatosis, particularly in those with concomitant obesity, meaning if the ultrasound is normal this may not exclude steatosis (8). One can consider ordering a complete abdominal ultrasound to assess for signs of portal hypertension, if this is a concern (8).

When should we order liver elastography (i.e. FibroScan)? Liver stiffness is a physical characteristic of the liver that increases with fibrosis severity as well as other processes such as passive congestion, marked inflammation, and infiltrative diseases (8). Elastography (i.e. FibroScan) is the most commonly used method to assess liver stiffness and can be used to exclude significant hepatic fibrosis (8). If there is concern for liver fibrosis, elastography is the preferred test over ultrasound.

THE BOTTOM LINE: MAFLD can be diagnosed in primary care by identifying 1 metabolic risk factor with right upper quadrant ultrasound identifying liver steatosis.

Back to the case: Your patient has metabolic risk factors (BMI of 35, pre-diabetes, and dyslipidemia), a low risk FIB-4 score, you have excluded other causes of elevated ALT, and ordered a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which reveals moderate steatosis.

Final diagnosis: MAFLD. Your plan is to optimize metabolic risk factors, and re-calculate FIB-4 every 2-3 years, unless risk factors change.

When should we refer to hepatology or gastroenterology?

When uncertain about diagnosis (e.g. suspected hemochromatosis, autoimmune hepatitis, etc.)

When uncertain about treatment

If intermediate or high risk of liver fibrosis

You can check out this helpful algorithm.

ReferencesMoriles KE, Zubair M, Azer SA. Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) Test. [Updated 2024 Feb 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559278/

Oh RC, Hustead TR, Ali SM, Pantsari MW. Mildly Elevated Liver Transaminase Levels: Causes and Evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Dec 1;96(11):709-715. PMID: 29431403.

Friedman LS. Overview of liver biochemical tests. In UpToDate Eidt Chopra SC, Li H (Ed). Wolters Kluwer. (Accessed January 25, 2025).

Kolber MR, Klarenbach S, Cauchon M, Cotterill M, Regier L, Marceau RD, et al. PEER simplified lipid guideline 2023 update. Prevention and management of cardiovascular disease in primary care. Can Fam Physician 2023;69:675-86

Nassir F, Rector RS, Hammoud GM, Ibdah JA. Pathogenesis and Prevention of Hepatic Steatosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2015 Mar;11(3):167-75. PMID: 27099587; PMCID: PMC4836586.

MDCalc. Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) Index for Liver Fibrosis. Available from: https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/2200/fibrosis-4-fib-4-index-liver-fibrosis#why-use

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) primary care pathway. Alberta Health. Available from https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/about/scn/ahs-scn-dh-pathway-nafld.pdf

Kanwal F, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Rinella ME. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Update and impact of new nomenclature on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidance on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2024 May 1;79(5):1212-1219. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000670. Epub 2023 Nov 9. PMID: 38445559.