Knee Pain in Adults: When to Order Diagnostic Imaging

Case: A 50-year-old female presents with a 6-month history of right knee pain.

History taking tips: assess location of pain, onset and duration (acute versus chronic), quality of pain, triggers (e.g. sitting, standing, resting, running), and history of trauma (e.g. motor vehicle collision, sports trauma, overuse injury), recent change in activity level (1). Acute versus chronic knee pain will help narrow down your differential diagnosis. Take into consideration the patient’s age (e.g. osteoarthritis is more common in older adults), sex (e.g. gout is more common in males), and risk factors (e.g. obesity, metabolic syndrome, purine-rich diet). Assess for systemic symptoms (e.g. fever, malaise, rash), to rule out the possibility of inflammatory knee pain (e.g. septic joint, autoimmune arthritis). Assess medical and surgical history (e.g. recent knee replacement?) Assess impact on quality of life and activities of daily living. Assess prior treatment modalities (e.g. physiotherapy, medications).

Back to the case: pain is diffuse and described as a “deep aching pain.” It’s worse with bending, stair-climbing, and worse at the end of the day. Rest does not improve it. Acetaminophen “takes the edge off.” She was an avid marathon runner in her 30s and reports a prior right knee injury that healed over time. There is no history of recent trauma or sudden change in activity level. She reports gradual weight gain over the last five years she attributes to poor diet and less physical activity. She has no past surgical history. Past medical history is significant for diabetes and dyslipidemia. She has been engaged in physiotherapy for the last 3 months without much improvement.

Physical exam tips: assess pain location (anterior, medial, lateral, posterior, or diffuse) to narrow down your differential diagnosis. As with any musculoskeletal presentation, remember to start with inspection, palpation, range of motion (passive and active), and special tests. Assess the patient’s gait and ability to weight bare (limping = able to weight bare).

Inspect for swelling, erythema, bruising, and gross deformity.

Palpate for tenderness, warmth, effusion, and nodules.

Assess ability to extend and flex the knee with passive motion and resistance.

Special tests are tailored to what your differential is. For example, if a patient presents with a blow to the lateral aspect of the knee, we want to assess for ligamentous laxity (rule out collateral ligament tears). Utility and diagnostic accuracy of special tests are well delineated here.

Back to the case: physical exam is significant for a BMI of 28, reduced range of motion and crepitus with right knee flexion and extension, and positive McMurray’s test. Remainder of the physical exam is normal. What is our differential diagnosis?

Diagnostic Approach to knee pain: knee pain is a common primary care presentation, affecting approximately 25% of adults – and prevalence is increasing (1). Knee pain has a long list of differential diagnoses that can be difficult to recall. Consider organizing your differentials by thinking of knee pain mechanisms:

Musculoskeletal: acute vs. chronic

Inflammatory: non-infectious vs. infections

These are 2 major buckets. Now let’s break it down further. When thinking of musculoskeletal causes of knee pain, we can think through the anatomy (e.g. is pain arising from collateral ligament injury or cruciate ligament injury?)

Now let’s review key hints on history and physical exam.

1. Musculoskeletal Knee Pain

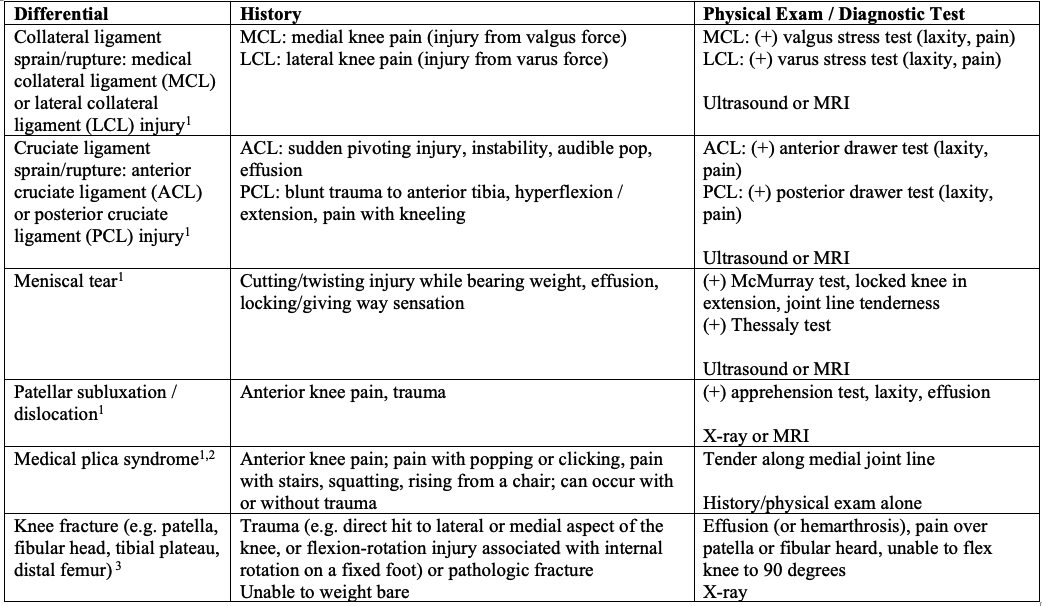

ACUTE KNEE PAIN

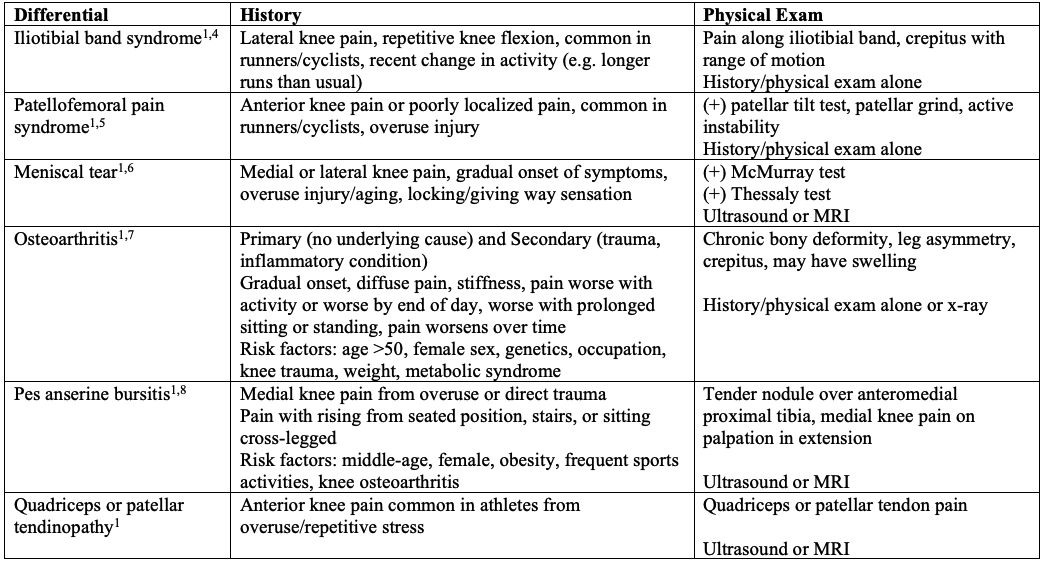

CHRONIC KNEE PAIN

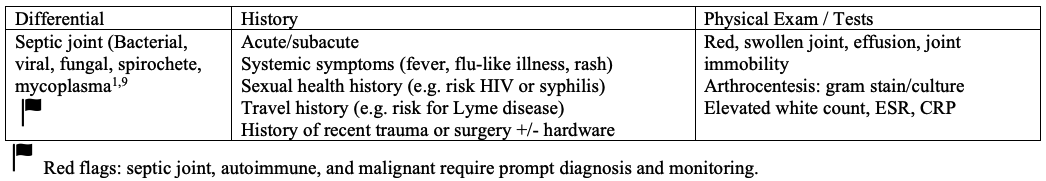

2. Inflammatory Knee Pain

NON-INFECTIOUS

INFECTIOUS

Back to the case: the most likely diagnosis is osteoarthritis of the right knee based on the history and physical exam alone. Is diagnostic imaging warranted at this time?

Diagnostic Imaging for Knee Pain

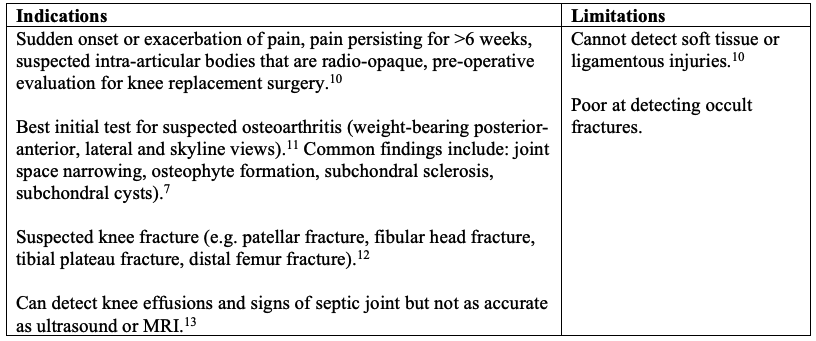

PLAIN RADIOGRAPHS

A note on the Ottawa Knee Rule: this is a validated clinical decision tool developed to allow clinicians to be more selective in use of plain radiography in the setting of acute knee injuries (16). It is a helpful point of care decision tool to determine whether knee radiograph is indicated. The rule is sensitive (good at ruling out the possibility of fracture when negative), but poor at ruling in fractures when positive (many false positives). It is available on MD CALC.

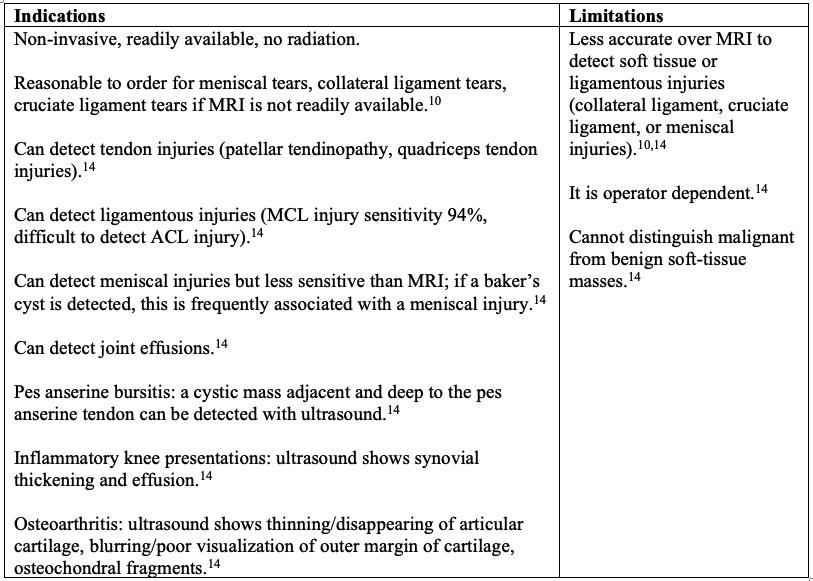

ULTRASOUND KNEE

MRI KNEE

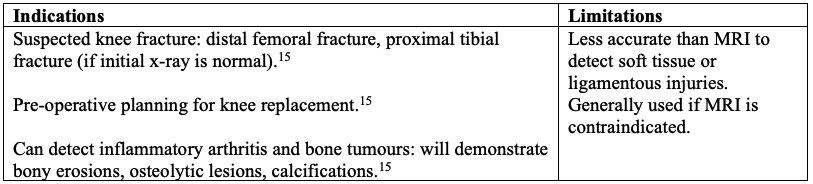

CT KNEE

Back to the case: a right knee radiograph is reasonable. The knee pain is affecting her quality of life and has not responded to 3 months of active physiotherapy. Radiograph can help confirm the suspicion of osteoarthritis and can be used for pre-operative planning if knee replacement surgery is being considered.

Key Take Home Points:

X-ray is our test of choice for suspected osteoarthritis and pre-operative surgical planning for knee replacement, as well as suspected fracture in the setting of trauma.

Ultrasound is our initial test of choice for suspected collateral ligament injury, meniscal injury, tendinopathy, and effusion.

MRI is our test of choice for soft tissue and ligamentous injuries not detected on ultrasound, occult fracture, and is typically reserved if surgical intervention is being considered.

Remember: will ordering this imaging test help narrow down my differential (or am I confident with my diagnosis from the physical and history alone), and will it change management (e.g. is my patient asking for knee replacement surgery for osteoarthritis?)

References AAF 2018: Bunt CW, Jonas CE, Chang JG. Knee Pain in Adults and Adolescents: The Initial Evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2018 Nov 1;98(9):576-585. PMID: 30325638.Casadei 2023: Casadei K, Kiel J. Plica Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Apr 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535362/Beutel BG, Trehan SK, Shalvoy RM, Mello MJ. The Ottawa knee rule: examining use in an academic emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2012 Sep;13(4):366-72. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2012.2.6892. PMID: 23251717; PMCID: PMC3523897.Hadeed A, Tapscott DC. Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome. [Updated 2023 May 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542185/Bump JM, Lewis L. Patellofemoral Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Feb 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557657/Hohmann E. Treatment of Degenerative Meniscus Tears. Arthroscopy. 2023 Apr;39(4):911-912. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2022.12.002. PMID: 36872031.Hsu H, Siwiec RM. Knee Osteoarthritis. [Updated 2023 Jun 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507884/Mohseni M, Mabrouk A, Li DD, et al. Pes Anserine Bursitis. [Updated 2024 Jan 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532941/Momodu II, Savaliya V. Septic Arthritis. [Updated 2023 Jul 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538176/Canadian Association of Radiologists. Canada. 2021-2022 [June 2024]. Available from https://car.ca/patient-care/referral-guidelines/Orthopedics. Choosing wisely [Internet]. [2018; June 15, 2024]. Available from https://choosingwiselycanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Orthopaedics.pdfExpert Panel on Musculoskeletal Imaging; Taljanovic MS, Chang EY, Ha AS, Bartolotta RJ, Bucknor M, Chen KC, Gorbachova T, Khurana B, Klitzke AK, Lee KS, Mooar PA, Nguyen JC, Ross AB, Shih RD, Singer AD, Smith SE, Thomas JM, Yost WJ, Kransdorf MJ. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Acute Trauma to the Knee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020 May;17(5S):S12-S25. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.01.041. PMID: 32370956.Knee series. Radiopedia [Internet]. [2023; June 15, 2024]. Available from https://radiopaedia.org/articles/knee-seriesULTRASOUND 2009 : Razek AA, Fouda NS, Elmetwaley N, Elbogdady E. Sonography of the knee joint(). J Ultrasound. 2009 Jun;12(2):53-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2009.03.002. Epub 2009 Apr 28. PMID: 23397073; PMCID: PMC3553228.CT Knee. Radiopedia [Internet]. [2024; June 15, 2024]. Radiopedia: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/ct-knee-protocol-1Stiell IG, Wells GA, Hoag RH, Sivilotti ML, Cacciotti TF, Verbeek PR, Greenway KT, McDowell I, Cwinn AA, Greenberg GH, Nichol G, Michael JA. Implementation of the Ottawa Knee Rule for the use of radiography in acute knee injuries. JAMA. 1997 Dec 17;278(23):2075-9. PMID: 9403421.